To be long in the tooth

This unflattering term alludes to the fact that a horse’s gums recede as it gets older, and transfers this same phenomenon to humans. This transfer is not very old, since until relatively recent times most adults who were old enough to experience gingival recession had lost most of their teeth. It dates back to the nineteenth century; the author William Thackeray used it in his novel The History of Henry Esmond, Esq. (1852), “She was lean and yellow and long in the tooth”.

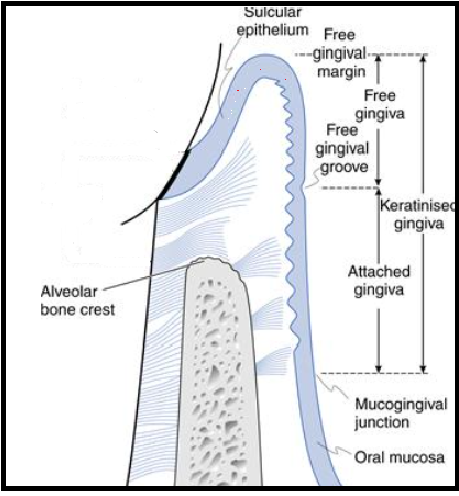

The attached gingiva

The attached gingiva is firm, resilient and tightly bound to the underlying alveolar bone and cementum by connective tissue fibres.

Gingival recession is common in a meaningful proportion of the adult population; it is present even in people with good oral hygiene. This suggests a complex array of causes (Joshipura et al. 1994) including anatomical and iatrogenic, as well as being closely associated with gingivitis and periodontal disease (Baker & Spedding 2002, Litonjua et al. 2005). The occurrence (gingival recession) increases in frequency with age; therefore, it is associated with age rather than a result of age. “Getting long in the tooth” is most likely due to loss of gingival attachment (Needleman 2015).

The significance is that all exposed root surfaces are at risk of root caries and this risk is greater in older dentate individuals. Regardless of the cause, gingival recession is increasing with age and root caries will increase as patients retain their teeth longer.

Geriatric patients residing in nursing homes are particularly vulnerable (Vigild 1989, Wyatt 2002, Simunkovic et al. 2005, Ferro et al. 2008) for a number of reasons including: polypharmacy, quantity and acid buffering ability of saliva, frequency of food intake, high use of food (especially fermentable carbohydrates) as a behavioural management tool, and lack of oral hygiene due to cognitive impairment.

Root caries anatomy

Root surfaces differ from enamel surfaces, due to root surfaces (dentine) having a lower mineral content and a higher amount of organic material (collagen). Because of the smaller size of the apatite crystals, root surfaces are highly receptive to mineral uptake in the oral environment (if there is good salivary flow with good acid buffering capacity). This explains why exposed root surfaces usually present a hyper-mineralised surface zone, the mineral content of which may be higher than that of sound unexposed dentine (Selvig 1969). In vivo studies have shown that topical treatments with fluoride may enhance mineral precipitation in root surfaces (Furseth 1970).

Periodontal treatment including surgery , aggressive scaling and root planning may break or remove this hyper-mineralised area exposing the dentine tubules causing hyper-sensitivity and a roughened area that can accumulate biofilm/caries. Periodontal treatment may be counterproductive for the clinician who prefers to conserve the hyper-mineralised root surface (Heasman et al. 2017).

Caries management

From a clinical perspective the integrity of the root surface lesion should remain intact by adopting non-invasive treatment. All root surfaces are at risk of root caries, but areas that retain the biofilm are particularly vulnerable, these include: the cemento-enamel junction, mesial and distal interproximal surfaces and along the margins of restorations, especially at the gingival margin if the restoration is overhanging.

Treatments

Fluoride derivatives, Ammonia based 38% SDF was advocated as a treatment to arrest and prevent new dentine caries (Rosenblatt at al. 2009). This was attributed to the bactericidal properties of silver and fluoride’s ability to facilitate hyper-mineralisation (Nyvad et al. 1997); studies (Zhang et al. 2013, Li et al. 2016) found, annual SDF treatment may promote lesion arrest. Supporters of SDF treatment for root caries often ignore the potential harmful side effects, namely the mildly painful chemical burns on the oral mucosa that may last up to 48 hours (Rosenblatt et al.2009). To circumvent this side effect Deutsch (2016) used a different type of silver fluoride to treat root caries; he used a water-based 40% silver fluoride and 10% stannous fluoride. The advantage of this silver fluoride/stannous fluoride combination is it didn’t cause gingival burns. This was applied on a 3 to 4 month basis to multiple active root caries in frail elderly patients without causing any discomfort; furthermore, Deutsch suggested this approach to be suitable in the treatment of cognitively impaired elderly with behavioural problems where conventional treatment can be challenging if not impossible.

Conventional operative treatment of root caries should be avoided, due to the relatively poor prognosis (Hu et al. 2005, Lo et al.2006, Gil-Montoya et al. 2014) The majority of conventional restorations fail, possibly due to patients having behavioural problems resulting in decreased ability to cooperate; limiting the operator’s visibility, access, poor salivary flow and acid buffering ability. Recently high –viscosity glass ionomer cements (example product GC Equia Forte TM) have become the preferred choice due to the chemical bonding to root surfaces.

The need for effective root-surface treatments is illustrated by data from the UK. It has been reported that the percentage of dentate adults in all age groups in the UK and particularly those over 55 is increasing significantly over the decades (Steele et al. 2000, Fuller et al 2011). Future projections using 1988 and 1998 data predicted around 43% of adults over 85 in 2008 would retain at least one natural tooth. The actual figure turned out to be 53% (Fuller et al. 2011) far exceeding expectations. Furthermore, in the UK, adults over 55 that were retaining at least 21 natural teeth had increased by approximately 10% each decade from 30% in 1978 to 63% in 2009. Over the same period the mean number of teeth/individual had risen from 16 to 21.2 (Fuller et al. 2011); if this trend continues it is estimated by 2030 80% of adults in the UK will have at least 21 teeth with a mean of approximately 25 teeth. Given these predictions and the worldwide increase in the ageing population; root caries is set to become a very serious health issue for the world’s elderly citizens.

References

Baker, P. & Spedding, C. (2002) The aetiology of gingival recession. Dent Update 29, 59 –62.

Deutsch, A. (2016) An alternate technique of care using silver fluoride followed by stannous fluoride in the management of root caries in aged care. Spec Care Dent 36, 85 –92.

Ferro, R., Besostri, A., Strohmenger, L., Mazzucchelli, L., Paoletti, G., Senna, A., Stellini, E. & Mazzoleni, S. (2008) Oral health problems and needs in nursing home residents in Northern Italy. Comm Health Dent 25, 231–236.

Frencken, J. E. (2014) The atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) approach can improve oral health for the elderly; myth or reality? Gerontology 31, 81 –82. ( Accessed June 2016)

Fuller, E., Steele, J., Watt, R. & Nuttall, N. (2011) Oral health and function – a report from the Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/ PUB01086/adul-dent-heal-surv-summ-them-the 1-2009-rep3.pdf Accessed June 2016.

Furseth, R. (1970) A study of experimentally exposed and fluoride treated dental cementum in pigs. Acta Odontol Scand 28, 833–850

Gil-Montoya, J. A., Mateos-Palacios, R., Bravo, M., Gonzalez-Moles, M. A. & Pulgar, R. (2014) Atraumatic restorative treatment and Carisolv use for root caries in the elderly: 2year follow-up randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 18, 1089-1095

Heasman PA, Ritchie M, Asuni A, Gavillet E, Simonsen JL, Nyvad B. Gingival recession and root caries in the ageing population: a critical evaluation of treatments. J Clinical Periodontol 2017; 44 (Suppl. 18): S178–S193. doi: 10.1111/ jcpe.12676.

Hu, J. Y., Chen, X. C., Li, Y. Q., Smales, R. J. & Yip, K. H. (2005) Radiation-induced root surface caries restored with glass-ionomer cement placed in conventional and ART cavity preparations: results after two years. Aust Dent J 50, 186–190.

Joshipura, K. J., Kent, R. L. & DePaola, P. F. (1994) Gingival recession: intra-oral distribution and associated factors. J Periodontol 65, 864–871.

Li, R., Lo, E. C. M., Liu, B. Y., Wong, M. C. M. & Chu, C. H. (2016) Randomized clinical trial on arresting dental root caries through silver diamine fluoride applications in community dwelling elders. J Dent 51, 15 –20.

Litonjua, L. A., Andreana, S. & Cohen, R. E. (2005) Toothbrush abrasions and noncarious cervical lesions: evolving concepts. CompendContin Educ Dent 26, 767– 768, 770-774, 776.

Lo, E. C. M., Loy, Y., Tan, H. P., Dyson, J. E. & Corbet, E. F. (2006) ART and conventional root restorations in elders after 12 months. J Dent Res 85, 929–932.

Needleman, I. (2015) Aging and the periodontium. In: Newman, M. G., Takei, H. H., Klokkevold, P. R. & Carranza, F. A. (eds). Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology, 12th edition, pp. 40–44, Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders.

Nyvad, B., ten Cate, J. M. & Fejerskov, O. (1997) Arrest of root surface caries in situ. J Dent Res 76, 1845–1853.

Rosenblatt, A., Stamford, T. C. & Niederman, R. (2009) Silver diamine fluoride: a caries “silverfluoride bullet”. J Dent Res 88, 116–125.

Selvig, K. A. (1969) The formation of plaque and calculus on recently exposed tooth surfaces. J Periodontol Res 4, S10–S11.

Simunkovic, S. K., Boras, V. V., Panduric, J. & Zilic, I. A. (2005) Oral health among institutionalised elderly in Zagreb, Croatia. Gerodontology 22, 238–241

Steele, J. G., Treasure, E., Pitts, N. B., Morris, J. & Bradnock, G. (2000) Total tooth loss in the United Kingdom in 1998 and implications for the future. Bri Dent J 189, 598–603..

Vigild, M. (1989) Dental caries and the need for treatment among institutionalized elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 17, 102–105.

Wyatt, C. C. L. (2002) Elderly Canadians residing in long-term care hospitals: Part II. Dental caries status. J Can Dent Assoc 68, 359–363.

Zhang, W., McGrath, C., Lo, E. C. & Li, J. Y. (2013) Silver diamine fluoride and education to prevent and arrest root caries among community-dwelling elders. Caries Res 47, 284– 290.